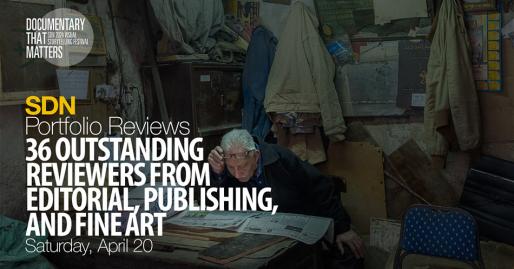

Meet with top photo editors, publishers, and curators

SDN is excited to announce the fourth SDN Online Documentary Portfolio Reviews. We have teamed up with leaders in the editorial, publishing, and fine art industries to review work of documentary and editorial photographers, offer constructive criticism, and to keep an eye out for new and talented photographers.

Click here for more information

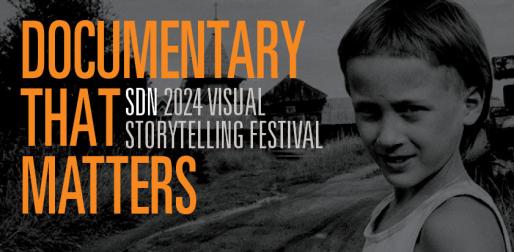

Virtual and in-person festival celebrating documentary photography with portfolio reviews, workshops, panels, exhibitions, and more.

Join us for the first SDN Visual Storytelling Festival bringing all of our spring 2024 programs under one banner. Whether you are a working photographer or engaged in documentary photography and photojournalism in other ways, this festival will offer outstanding programming for everyone.

Click here for more information

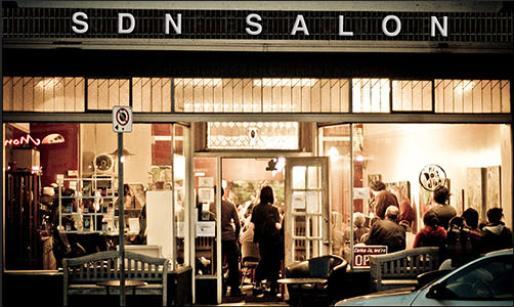

The Under 30 Salon.

Seeking presenters who are 30 or under. Attendees of all ages encouraged.

The SDN Salon is an informal networking opportunity for SDN members to present and view documentary photography. Bring a cup of tea or coffee (or absinthe if you prefer), your work in progress or portfolio, ideas to discuss, or just yourself. This virtual meeting is an opportunity to share your work, view work of others, and to talk about any issues that are relevant to being a documentary photographer in 2024.

Click here to register to attend or submit work.

SDN is excited to announce the fourth SDN Online Documentary Portfolio Reviews. Leaders in the editorial, publishing, and fine art industries will review work of documentary and editorial photographers, offer constructive criticism, and to keep an eye out for new and talented photographers.

Part of the SDN 2024 Visual Storytelling Festival

Part of the SDN 2024 Visual Storytelling Festival

Photos by Ed Kashi.

ZEKE magazine presents the best of global documentary photography delivered to your door, and to your digital device, twice a year. Each issue presents outstanding photography from the Social Documentary Network on topics as diverse as the war in Syria, the European migration crisis, the Bangladesh garment industry, and other issues of global concern.

Click here to subscribe

Click here to visit the SDN YouTube Channel

Sign up to receive notifications about our documentary photography programs and events including Call for Entries, SDN Salon, Documentary Matters, SDN Education, SDN Reviews, ZEKE magazine and more...