J O I N U S : D O C U M E N T A R Y M A T T E R S

Images of Conflict and Peace

Panel Discussion on Photographing Peace Around the World

Wednesday, June 8, 2:00-3:45 pm ET via Zoom

‘Peace means living a calm life’ — Patrick Shyaka, Rwandan genocide survivor’s child. Photo by Carol Allen Storey.

“Images of Conflict and Peace” is panel with four photographers and a scholar discussing a curated collection of exhibits from the Social Documentary Network archives that address the topic of conflict and peace. This body of photography was selected based on both its geographic location and subject matter. The project and panel were built to parallel the subject matter in panelist Dr. Lauren Walsh’s NYU Gallatin seminar Photographing Peace. The four areas of focus are Bosnia & Herzegovina, Rwanda, Colombia, and the United States (more specifically, the summer of racial justice in 2020). These four areas may be completely different in terms of location, yet they create an overarching conversation on peace and how it is depicted in photography.

Peace photography, a fairly recent subset of photojournalism, takes on an advocacy role by utilizing the camera as a tool to spread awareness and hold bad actors accountable. Instead of simply photographing what they see, peace photographers will use pictures to help people understand the political, economic, and social systems causing the violence depicted elsewhere. Our panelists were selected based on their different depictions of peace in their imagery, just as varied as geographic locations photographed.

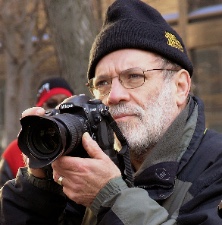

Steve Cagan

Colombia

Steve Cagan has been practicing activist photography since the mid-1970s. His major work is in what is often called documentary, but what Steve prefers to call activist or socially engaged photography. He’s most concerned with exploring strength and dignity in everyday struggles of grassroots people resisting their pressures and problems. Major projects include: factory closings in Ohio; Indochina; Nicaragua; El Salvador; and Cuba; and “Working Ohio,” an extended portrait of working people. Current major project, since 2003: “El Chocó, Colombia: Struggle for Cultural and Environmental Survival,” on the threatened rainforest and human cultures there. He’s exhibited and published on four continents. Awards include two Fulbright Fellowships, and fellowships from National Endowment for the Arts Ohio Arts Council Fellowships and New Jersey Arts Council. Taught at Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University, 1985-1993. Co-author of This Promised Land, El Salvador, (1991 Book of the Year Award of Association for Humanist Sociology). In 1991, named “Teacher of the Year” at Rutgers University. The third major event that spring was being denied tenure at Rutgers.

Steve Cagan has been practicing activist photography since the mid-1970s. His major work is in what is often called documentary, but what Steve prefers to call activist or socially engaged photography. He’s most concerned with exploring strength and dignity in everyday struggles of grassroots people resisting their pressures and problems. Major projects include: factory closings in Ohio; Indochina; Nicaragua; El Salvador; and Cuba; and “Working Ohio,” an extended portrait of working people. Current major project, since 2003: “El Chocó, Colombia: Struggle for Cultural and Environmental Survival,” on the threatened rainforest and human cultures there. He’s exhibited and published on four continents. Awards include two Fulbright Fellowships, and fellowships from National Endowment for the Arts Ohio Arts Council Fellowships and New Jersey Arts Council. Taught at Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University, 1985-1993. Co-author of This Promised Land, El Salvador, (1991 Book of the Year Award of Association for Humanist Sociology). In 1991, named “Teacher of the Year” at Rutgers University. The third major event that spring was being denied tenure at Rutgers.

Glenn Ruga

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Glenn Ruga is a photographer, graphic designer and curator. He founded the Social Documentary Network (SDN) in 2008 as a platform for a global community of documentary photographers to present their work online. In 2015, Ruga launched ZEKE: The Magazine of Global Documentary, a print and digital magazine presenting the best stories from the Social Documentary Network. As a photographer, he has created traveling and online documentary exhibits on the struggle for a multicultural future in Bosnia, the war and aftermath in Kosovo, and on an immigrant community in Holyoke, Mass. From 1993 through 2009, Ruga was the founder and president of the Center for Balkan Development, a non-profit organization established to help stop the genocide in Bosnia and create a just and sustainable future in the former Yugoslavia. From 2010-2013, Ruga was the Executive Director of the Photographic Resource Center (PRC) at Boston University.

Glenn Ruga is a photographer, graphic designer and curator. He founded the Social Documentary Network (SDN) in 2008 as a platform for a global community of documentary photographers to present their work online. In 2015, Ruga launched ZEKE: The Magazine of Global Documentary, a print and digital magazine presenting the best stories from the Social Documentary Network. As a photographer, he has created traveling and online documentary exhibits on the struggle for a multicultural future in Bosnia, the war and aftermath in Kosovo, and on an immigrant community in Holyoke, Mass. From 1993 through 2009, Ruga was the founder and president of the Center for Balkan Development, a non-profit organization established to help stop the genocide in Bosnia and create a just and sustainable future in the former Yugoslavia. From 2010-2013, Ruga was the Executive Director of the Photographic Resource Center (PRC) at Boston University.

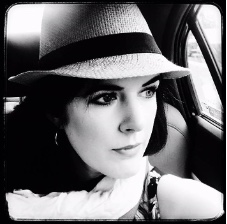

Carol Allen Storey

Rwanda

Carol Allen-Storey is an award-winning documentary and reportage photographer specializing in chronicling complex humanitarian and social issues. In 2009 Storey was appointed a UNICEF ambassador for photography. A native New Yorker, Carol resides in London. Her oeuvre has been exhibited and published internationally. Her solo exhibitions include: ‘The AMAHORO Generation’, ‘CROSSINGS’, ‘TEENS and the Loneliness of AIDS’, ‘FRACTURED LIVES’, ‘Children of Hope’ ‘Anything Is Possible’, ‘The Vanishing Assets of Africa’ and ‘The Savagery and Poetry of Africa’. Storey has won and shortlisted for multiple international awards. Recently she won 1st place for the Julia Margaret Cameron Award for three consecutive years: In 2022 with her series ‘Rape as a Weapon of War’. In 2021, with her series ‘Out of the Shadows’ and in 2020 with her series ‘Healing the Scars of Genocide’. Some others include: The Taylor-Wessing 2009, 2011, 2013 and 2016. Winner for the Color Awards 2021and 2020, first prize in the series category for the IPPA Awards 2019, 1st prize series, the Association of Photographers portrait award, finalist 2019, Lens Culture B&W Award finalist, 2019, The IPA 2018, 2nd prize editorial. 1st Prize Act of Kindness International Award, the Renaissance Award, The Moving Walls exhibition touring Europe. Storey is a graduate with distinction of the Central St. Martins, Master Photography programme, 2000. Further degrees include BA, Syracuse University, MA Columbia University.

Carol Allen-Storey is an award-winning documentary and reportage photographer specializing in chronicling complex humanitarian and social issues. In 2009 Storey was appointed a UNICEF ambassador for photography. A native New Yorker, Carol resides in London. Her oeuvre has been exhibited and published internationally. Her solo exhibitions include: ‘The AMAHORO Generation’, ‘CROSSINGS’, ‘TEENS and the Loneliness of AIDS’, ‘FRACTURED LIVES’, ‘Children of Hope’ ‘Anything Is Possible’, ‘The Vanishing Assets of Africa’ and ‘The Savagery and Poetry of Africa’. Storey has won and shortlisted for multiple international awards. Recently she won 1st place for the Julia Margaret Cameron Award for three consecutive years: In 2022 with her series ‘Rape as a Weapon of War’. In 2021, with her series ‘Out of the Shadows’ and in 2020 with her series ‘Healing the Scars of Genocide’. Some others include: The Taylor-Wessing 2009, 2011, 2013 and 2016. Winner for the Color Awards 2021and 2020, first prize in the series category for the IPPA Awards 2019, 1st prize series, the Association of Photographers portrait award, finalist 2019, Lens Culture B&W Award finalist, 2019, The IPA 2018, 2nd prize editorial. 1st Prize Act of Kindness International Award, the Renaissance Award, The Moving Walls exhibition touring Europe. Storey is a graduate with distinction of the Central St. Martins, Master Photography programme, 2000. Further degrees include BA, Syracuse University, MA Columbia University.

Dr. Lauren Walsh

Dr. Lauren Walsh, Professor at New York University and Director of the Gallatin Photojournalism Lab, is the author of Conversations on Conflict Photography (2019) and Through the Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter (2022), co-author of Shadow of Memory (2021) on the Bosnian War, and editor of Macondo: Memories of the Colombian Conflict (2017). She is a leading expert on the visual coverage of conflict and crisis, and teaches courses on peace journalism.

Dr. Lauren Walsh, Professor at New York University and Director of the Gallatin Photojournalism Lab, is the author of Conversations on Conflict Photography (2019) and Through the Lens: The Pandemic and Black Lives Matter (2022), co-author of Shadow of Memory (2021) on the Bosnian War, and editor of Macondo: Memories of the Colombian Conflict (2017). She is a leading expert on the visual coverage of conflict and crisis, and teaches courses on peace journalism.

Shoun Hill

United States

Shoun Hill is a visual journalist/educator living between New York City and Lincoln, Nebraska. Originally from Frederick, MD., Hill began photographing professionally in 1993 for The Gleaner in Henderson, KY., after getting his Master of Arts degree from Ohio University. At the present time, Shoun is an Assistant professor at the College of Journalism & Mass Communication at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln teaching photojournalism and multimedia. He has worked as a staff photographer for newspapers in Memphis, Tenn., and Orlando, Fla., as well as being a photo editor on the National Desk of the Associated Press in NYC. While a staff photographer, Shoun photographed Super Bowls, NBA basketball games, and presidential elections. He has also been a part of gallery shows in Ohio, Florida, Illinois, and New York. Shoun’s documentary film on African American farmers, “I’m Just a Layman in Search of Justice-Black Farmers Fight Against USDA”, was selected as the People’s Choice at the Denton Black Film Festival as well as an Honorable Mention. The film was also an Official entrant in the IMPACT DOCS, The Seattle Black Film Festival, Docs Without Borders, to name a few. Shoun is married to Debra Walton-Hill, a Broadway and TV actress, performer and director.

Shoun Hill is a visual journalist/educator living between New York City and Lincoln, Nebraska. Originally from Frederick, MD., Hill began photographing professionally in 1993 for The Gleaner in Henderson, KY., after getting his Master of Arts degree from Ohio University. At the present time, Shoun is an Assistant professor at the College of Journalism & Mass Communication at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln teaching photojournalism and multimedia. He has worked as a staff photographer for newspapers in Memphis, Tenn., and Orlando, Fla., as well as being a photo editor on the National Desk of the Associated Press in NYC. While a staff photographer, Shoun photographed Super Bowls, NBA basketball games, and presidential elections. He has also been a part of gallery shows in Ohio, Florida, Illinois, and New York. Shoun’s documentary film on African American farmers, “I’m Just a Layman in Search of Justice-Black Farmers Fight Against USDA”, was selected as the People’s Choice at the Denton Black Film Festival as well as an Honorable Mention. The film was also an Official entrant in the IMPACT DOCS, The Seattle Black Film Festival, Docs Without Borders, to name a few. Shoun is married to Debra Walton-Hill, a Broadway and TV actress, performer and director.

Meg Gray, Moderator

Meg Gray is a rising senior at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study. As the daughter of two US diplomats, she spent her upbringing on three different continents and five different countries. Outside of her work at the Social Documentary Network, Meg is an editor for Gallatin’s student-produced Embodied Magazine. Her writing has been published in SkidNews, Skidmore Theater Living Newsletter, and Saratoga Living Magazine.

Meg Gray is a rising senior at New York University’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study. As the daughter of two US diplomats, she spent her upbringing on three different continents and five different countries. Outside of her work at the Social Documentary Network, Meg is an editor for Gallatin’s student-produced Embodied Magazine. Her writing has been published in SkidNews, Skidmore Theater Living Newsletter, and Saratoga Living Magazine.

Four areas of conflict

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Before the war in Bosnia & Herzegovina that began in 1992, there was the multi-ethnic state of Yugoslavia. The three main groups in the country – Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks – were divided not only by ethnicity but religion as well. The war lasted three long years, providing ample time for renowned international photojournalists to capture the realities of the conflict. Photographers who were given exclusive access to the bloody clashes by armed groups used their images for an especially important purpose: documentation. Photographs were presented at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague as evidence against the leaders of the conflict.

The 1995 Dayton Peace accords led to the end of the Bosnian war, at least formally. Internal conflict still persists, not only in the form of direct violence, but also in the lack of opportunity that many young Bosnians face in their home country. Reconciliation has not necessarily been achieved fully, which can be seen in photographs taken in Bosnia today, many of which still center on residual conflict from the war.

Rwanda

Rwanda, on the other hand, only experienced 100 days of killing in 1994; those few short months have gone on to define the country’s history. The official beginning was April 6, when Rwanda’s President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, also carrying Burundi’s president. The majority ethnic group, the Hutus, began targeting the Tutsis. This conflict is neither ancient or tribal. It began with the introduction of Europeans in Rwanda, who strictly classified and divided the population based on perceived ethnic differences. Genetically, the Tutsis and Hutus are the same, but their differences were expanded with colonial governmental action. The exact number of people killed during the genocide is unknown, but it’s approximated in the high hundred thousands. Millions more fled the country to neighboring states Burundi, Uganda, Tanzania, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, inciting another yet humanitarian crisis.

The war in Rwanda was a a textbook example of genocide, but a unique example of reconciliation. Rwanda developed a unique solution, Gacaca courts, which were run by local communities and served as one of the main ways that those who committed genocide were tried. Perpetrators of violence who confessed and apologized for their crimes in Gacaca courts received lighter sentences than those who were found guilty, incentivizing honesty and forgiveness. The conflicts in both Rwanda and Bosnia are drastically different, especially in terms of reconciliation. Many of the exhibits in Bosnia feature remnants of the war, while images from Rwanda may appear more hopeful, more distant from the devastating genocide.

Colombia

The conflict in Colombia is the longest – and arguably the most difficult to understand. It lasted over 50 years and primarily involved the Colombian government’s army and paramilitary groups like United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC, right-wing), Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP, left-wing guerilla group), the National Liberation Army (ELN), M-19, the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and many other smaller groups. From the 1960s onwards, when guerilla communist groups began forming and gaining power, different parts of the country were under the control of various armies, segmenting the nation. Because of the violence that occurred, half a million people were displaced in Colombia, with another 76,000 missing and never located. The Colombian cartels became another complicated player to the mix, employing their own armed forces to protect their business infrastructure.

The two largest players were the Colombian government and the FARC, who agreed to a ceasefire in 2016. A ceasefire is easier to achieve than social peace, something that Colombia still lacks. The FARC is still operating, though it is no longer attacking the government, and maintains its bases in the Colombian jungles. Very few photographers have gotten access to the inner workings of the group, but those who did share images of a persisting conflict.

United States

If looking at racial justice through the lens of the first slaves brought to the American colonies in 1619, the United States has the longest conflict out of these four countries in our panel. Hundreds of years of slavery, structural inequalities, and systemic racism cultivated in the summer of 2020’s racial justice protests, one of the most impressive examples of organized activism in American history. The horrific deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd woke up many Americans to the violence that BIPOC people in this country experience on a daily basis. It is important to make sure peace is contextual – analyzing the peace photography in one’s own country can be exceptionally revealing. The United States has had its own conflicts to resolve and a corresponding collection of peace photography documenting these struggles. The photographers selected here depict the resilience, hope, fear, anger, and love that demonstrators shared when exercising their first amendment rights, even during a global pandemic.

Some of the only remnants of these conflicts – beyond the memories living with survivors – are photographs. Images are what we have to make sense of these events that we lived through, and especially the ones we didn’t. Peace, as well as peace photography, takes many forms including those that we do not always recognize at first. It is more than simply a lack of violence; it is also the continual effort to make the world a more just place for everyone.